Enrolling in the Vienna and London study abroad program, I was most intrigued to see how the two classes Architecture in the 20th Century and the History of Psychoanalysis would complement each other. My understanding of architecture encompassed only specific unique styles from different times. For example, I understood that pointed arches were a part of Gothic architecture. My intuition on psychoanalysis was even more limited because I thought it simply involved different ways of thinking, which seemed more behavioral. Putting these two preconceptions together, my initial prediction was that the theories presented from the psychoanalysis class embodied a period of time in the 20th century, similar to how humanism defined the Renaissance era. With these theories, I thought that one would then be able to identify the architecture of that period because the architecture styles would reflect those very theories, which could build in me a strong appreciation for such a particular style. Then, I began to think to myself that was a silly idea because there is no “Psychoanalytic Period,” but I still thought that the intersection of the two classes would come as the architecture style mirroring the ideas of psychoanalysis.

Through the course of both classes, I have learned that the two are related in that we are looking at architectural structures and sites through the lens of purpose, instead of style and ornamentation. Instead of analyzing the various types of embellishment, the greater questions were why did the architect include such ornaments, and are they essential to the beauty of a structure? We arrived at this perspective by studying Freud’s theory of the unconscious which he believed that if properly understood could help people resolve their problems. Some examples of unconscious activity include dreams and instincts, and Freud would have his patients share all they could remember in order to see what is going on in their unconscious where he could pinpoint potential sources of their problems. I learned that this process is known as the analysis. Applying this mode of thinking to appreciating architecture, one would dig deeper to find the more subtle details and the importance of such buildings to see how they reflect how people thought, instead of taking buildings for how they appear outwardly or say they are intended for. This led to common themes that we discussed in class which were erasure, commemoration, and identity. The Bedlam Hospital at the Liverpool Station in London and the University of Vienna in Austria offer special venues to survey and examine these different themes to discover the greater purpose in their construction.

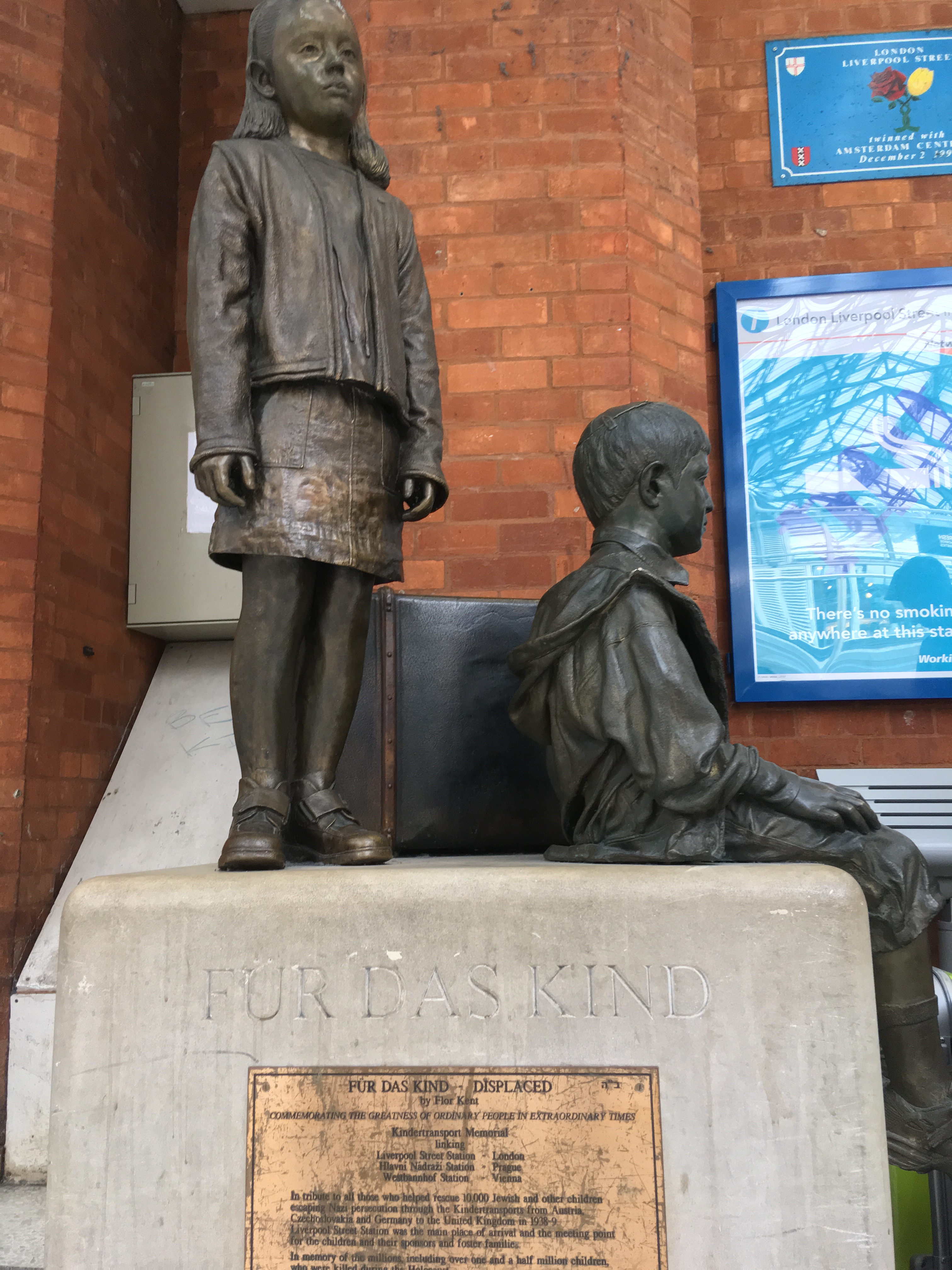

In London, the prime example of erasure of a regrettable history was the history of the Bedlam Hospital being transformed into the Liverpool Street Station area. The Bedlam Hospital was London’s first mental institution erected in the 1200’s. The “Building Bedlam – Bethlem Royal Hospital’s early incarnations” article offers context on the hospital noting that “there were no other hospitals for the insane in Britain at the time, or indeed many hospitals of any kind. The very term ‘hospital’ had not yet become so exclusively the property of a medical establishment and was still being used with its broader meaning of a place of hospitality… a place for the sick.” However, upon walking to the site of the Bedlam Hospital at the Liverpool station, one would not have had any indication that a hospital used to exist there. It appeared to resemble the typical tube station in London, but it is like doing an Easter egg hunt trying to find symbols and remnants of the late hospital. There was a small plaque that recognized the Bedlam Hospital about the size of two textbooks which was another small detail among many other busy eye-catching ones in the grand station. Another example of a small detail in the station is a statue of two children who fled from Germany during World War II and arrived at the station. Such pieces, whether good or bad, are not highlighted in the crowded area that would properly commemorate the hospital. The function of the space shifted to be exclusively a tube station, and only a very small percent of on-goers would have awareness of what the space used to be.

It was no surprise to later find that the Bedlam Hospital is “associated with scandal” because it was the site where many unwell people were tortured or manipulated. As the “Building Bedlam – Bethlem Royal Hospital’s early incarnations” article notes, “the layout of the hospital introduced the need for containment or confinement. To modern eyes the plan seems most closely allied to that of prisons, and in particular the model prisons of the nineteenth century.” Modern architects are able to determine that the hospital more resembled a prison which further reveals unconscious sentiments towards the mentally ill likening them to inmates locked confined in prison. The hospital became less of a place of hospitality where people would receive treatment and help, but instead it was a place to separate and remove seemingly the “defective and incompetent.” It was not a proud piece of London history, so one can understand why the hospital was covered up and replaced by an almost entirely new building. This made me think about the conflict between recognizing one’s past and whether places like this were trying to be concealed from the public eye or if it simply got left behind because modernization no longer had a place for it. However, I think that it is purposefully being shoved to the side and hidden because architects and leaders are able to properly dignify special people and places with grand statues and other large structures, not merely miniature plaques and statues. It did not seem right to hide such a dark page of history, but perhaps once one learns from their past, it is okay to.

Similarly, one can see how Vienna not only attempts to erase its past association with Germany but further to help define its national identity. In Cordileone’s “The Austrian Museum for Art and Industry: Historicism and National Identity in Vienna 1863-1900,” she describes how there is a connection between style in arts and in political views. In the example she gives, northern German Renaissance style became “associated with kleinduetch nationalism” (123). This is significant because it demonstrates how architectural style can influence and support specific public political sentiments. Austria took this to practice by “putting forward their local interpretation of the Italian Renaissance as a suitable visual for [itself]” (124). This new, unique style that the Austrians were trying to manufacture and develop for themselves would help it distinguish its own identity from the prominent power in the German Republic. As Cordileone notes, the larger goal was to “improve public taste.” With these objectives in mind, one can see how an improved sense of Austrian art would pay great dividends economically through commercial success abroad at international exhibitions. The way that Austria would go about attaining these goals was to acquire art from all over the world and put them all in grand museums and galleries that people from all over would flock to. This was their way of branding themselves and putting their name on the map despite being viewed as a little brother to big brother Germany. Ramping up their art department was their way to stand up to Germany because they did not have the capabilities to do so militarily. Another effect of this shift in architectural purpose would be an increased sense of patriotism and national identity among citizens for their country knowing that they have arguably the most beautiful architecture and art in Europe.

Reflecting on the context of the history of Austria and its architecture in comparison to London’s erasure of the Bedlam Hospital, I viewed Vienna’s approach to be a much more optimistic view of erasing the past. This was my impression because Vienna ‘erases’ its historical ties to Germany pre-1900s in order to help craft its own national identity apart from Germany, whereas the Bedlam Hospital was simply displaced by a more modern use of the space in the Liverpool Tube Station. I understood Austria’s goal to create its own identity by challenging Germany in the realm of art instead of combat as it being crafty to assert itself in the international spectrum which is an honorable act to take when someone is infringing on another’s potential and ability to act autonomously, as Germany was to Austria. Furthermore, one could view Austria’s initiative to set its artistic standards as a way to elevate and uplift its people. Again, analyzing its beautiful architecture from a purpose perspective, the elegance would build a seemingly distinguished atmosphere around the structure. I experienced this feeling of being in a fancy building at the University of Vienna.

The classy atmosphere at the University of Vienna made me feel like I had to behave with more discipline, and the impression it left on me resembled the wide-spread effect that Austria would have wanted its revamped art initiative to have on its citizens. Roaming the silent empty halls, there were tall wide arches, untainted white walls, and shiny reddish-brown tile floor surface. It really reminded me of the typical high school one would see in movies, but there was no trash or rowdy behavior from young, immature students. The beautiful architecture, accompanied with the superb upkeep disseminated that elegant, classy atmosphere, and while I walked through the halls and exploring the different rooms, I experienced a feeling of care for my surroundings because I did not want to disrupt the peace. There was a particularly memorable moment when walking through a computer lab where one girl was passing by as well and she banged her leg on the corner of the table and almost fell. All thirty people in the room turned around to glare at whoever interrupted the prior tranquility. Another way the University of Vienna crafts a classy atmosphere is by surrounding the grass atrium with a lot of busts of dignified alumni, notably Sigmund Freud. Apart from commemorating such famous products of the university, the placement of the statues could be utilized to inspire current students to realize that they can do great things and make a name for themselves, just like they did. In effect, the pedigree of the university as an institution would rise which would allow it to attract the best students from all over the world.

After the study abroad experience, I went home to Arizona to prepare for another year Community Assistant training at Vista del Sol residential hall at Arizona State University. My involvement with housing over the last year inspired me to do Part II of this capstone project on the history of Greek life on campus. There is a huge stigma with Greek life and partying at Arizona State that I wanted to investigate further because even before going to school here people would always refer to it as party school and advise me, “not to party too much!” When I came to campus in 2017, there was no Greek row with all the fraternities that many other colleges had, but I heard there used to be one but it had been torn down just 5 years prior. I thought this was a really good opportunity to dig deeper and find out how Arizona State University became infamously known as a party school across the country, and learning more about the history of Greek life as a residency on campus would be a unique outlet to learn how the label came to be prominent.

This article titled “Alpha Drive Construction: The Lost Community of ASU” by Keating offers a more objective description of the old fraternity community by analyzing the architectural design and history of the its construction and demolition. The site of Arizona State University’s Greek row known as Alpha Drive was in the northeast corner of campus on University Drive and Rural Road. There were thirteen fraternity houses situated in this region, and it was in the 1960s when the school began to build them for what was at the time 18 percent of male students who were involved in fraternity life. There was the Adelphi complex that housed five of the thirteen fraternities, but it was not large enough for everybody, having such a great presence on campus, school administration wanted to “maintain a form of control and supervision over the sometimes unruly and rowdy fraternities that primarily hosted functions at private off-campus locations.” The administrators contracted different architects to design the different houses, and they were able to display “distinctive sleek geometries, contrasting materials, minimal ornament, and functional forms that characterized mid-century architecture. Keaton notes that this style reflected a “modernist sensibility” which doubled the size of campus. While this was a massive expansion for Arizona State for the time, Alpha Row was able to maintain a low-density feel by spacing the different houses out across 13 acres. Keaton offers his opinion on the structural significance of the massive size of Alpha Drive saying that “for more than forty years, [it] served as a hub for all fraternity functions, but development and maintenance pressures, as well as skepticism about the role of fraternities at ASU and on college campuses in general, worked against these historic buildings.” Such details ultimately led to its demolition in 2012. This article effectively introduces how Alpha Drive appeared from the outside and the original purposes it served (“Alpha Drive Construction: The Lost Community of ASU”).

Another article I read titled “Reforming Greek Life: Alcohol-fueled incidents spur concern, change,” authors Richard Ruelas and Anne Ryman explore specific occurrences that impacted the fraternities’ departure from campus. In one of them, they describe a crowded setting where a fire blazes at a Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity party on Friday night. Paramedics and police arrive to the scene to calm scene, as they see one student pouring more alcohol into the fire, but in effect the fire flared out and caught on to one woman, and her legs began to burn. They describe the gruesome sequence as she falls to the ground and the paramedics roll her back and forth to put out the fire. This woman who got received severe burns was a 17-year-old high school student from California who came to Arizona State University to visit a friend. The two underage friends were also drinking at this fraternity party. The fallout of this bonfire incident ended with upset police officers who told detectives that fraternity members used social media to change the narrative that the girl had fallen into the fire or that they man who threw alcohol into the fire was not a member of the fraternity. It is such situations that involved lots of dangerous, sometimes deadly, crimes, especially those involving minors, coupled with a lack of responsibility that made ASU fraternities notorious with some being expelled and no longer acknowledged by Arizona State (“Reforming Greek Life: Alcohol-fueled incidents spur concern, change”).

Today, one could drive by the large 13-acre lot where Alpha Drive used to reside and see nothing but large cranes, mounds of dirt, and lots of construction. Since the houses were torn down in 2012, stadiums and parking lots have taken their place, and the current construction is for more apartment housing, hotels, offices, and stores. To replace Alpha Drive, the Greek Leadership Village was opened in 2018 across the street on Terrace and Rural Road. These are built in townhome style, which allows more people to be in the space similar to regular dorms on campus, however each Greek organization has its insignia and letters outside their respective areas. The space as a whole is intended to offer a mix of university housing and off-campus housing that may interest some students. Furthermore, they even have “Greek Ambassadors” who are similar to my role as a community assistant where we help ensure safety for our residents. Even President Crow said that there is an increased focus on “leadership development” in the Greek organizations, which he may hope builds a stronger sense of responsibility and accountability that some previous ones used to lack (“From the ground up, the rebuilding of Greek housing at ASU”).

The damage of Alpha Drive is still seen on the university’s tainted image, as Arizona State is still widely known as a party school. However, demolishing Alpha Drive and placing a more organized, intentionally sound Greek Leadership Village fits President Crow’s efforts to uplift and elevate the school’s stature. One can see how he learned from the institution’s past to shift the direction and trajectory of the school. He even enforced an unpopular but effective dry campus policy such that no one could drink or smoke on campus regardless of their age. These are the tough decisions that leaders have to make to lead their respective peoples or organization towards improvement and progress. On the outside to many students, it may appear that the school is giving us a hard time and revoking fun activities for young people, however diving beyond that, there may be a greater vision in mind where Arizona State is a distinguished center and foundation for scholars all over the world to flock to collaborate and create change. Through this project and studying architecture coupled with psychoanalysis, I have learned to look past what actually happened or what was said in different decisions or events and instead entertain and ponder why such things occurred in order to understand the social construction that leaders and people around us are trying to craft.

Works Cited

“Building Bedlam – Bethlem Royal Hospital’s early incarnations.” Historic Hospitals. February 13, 2016. Retrieved from https://historic-hospitals.com/2016/02/13/building-bedlam-bethlem-royal-hospitals-early-incarnations/

—

Cordileone, Diana Reynolds. “The Austrian Museum for Art and Industry: Historicism and National Identity in Vienna 1863-1900.” Austrian Studies. Vol. 16, From “Ausgleich” To “Jahrhundertwende”: Literature and Culture, 1867–1890 (2008), pp. 123-141. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/27944880.

—

Keating, Austin. “Alpha Drive Construction: The Lost Community of ASU.” Salt River Stories. Retrieved from https://saltriverstories.org/items/show/363?tour=32&index=1.

—

Ruelas, Richard and Ryman, Anne. “Reforming Greek Life: Alcohol-fueled incidents spur concern, change.” AZCentral. September 8, 2013. Retrieved from http://archive.azcentral.com/community/tempe/articles/20130828asu-fraternities-off-campus-issues.html.

—

Yaghsezian, Savanah. “From the ground up, the rebuilding of Greek housing at ASU.” The State Press. November 9, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.statepress.com/article/2016/11/sp-magazine-asu-plans-to-add-more-greek-life-housing.